June 15, 2012

The things I am looking forward to the most about coming home (besides family and friends) are washing machines and organized trash disposal. When I first arrived in country, I immediately noticed the black plastic bags everything, seemingly decorating the landscape as polka dots. I swore I would never come to littering. And I tried so hard at first, but it’s hopeless. People laugh at you if you try to save trash until you find a garbage can (likely not until you get home). Everything here is put into plastic bags to sell –you drink water from saches, market snacks are sold in saches or wrapped in paper. And there are no trash cans anywhere. But even more than organized trash disposal, I miss washing machines. I can’t wait to have all of my clothes except for the clothes I’m wearing be clean. Actually, I just can’t wait to have clothes that are actually clean. Before leaving for Peace Corps, someone told me they had read or heard a PCV say that her clothes had never been so clean and white because she had to scrub them herself and she could just see the dirt coming out. I find this entirely false. Yes, you scrub yourself and yes, you can see the dirt coming out, but you have to scrub really hard! I can’t get my whites white again (in fact, I just don’t wear white anymore) and it’s exhausting! I only kind of get my clothes clean. And even if they are clean, they get dusty and sweaty within 10 minutes of wearing them again, if they haven’t already gotten dusty sitting in my dresser.

As I’m getting ready to leave, things are already becoming bittersweet. Even as I was washing my laundry yesterday, I had a moment of “Oh this isn’t that bad,” (that thought didn’t last more than 2 minutes though). I can’t believe how fast it’s gone by – I will be leaving my village in just over a month! At this point, I’ve started to reflect; was it what I expected, was is what I wanted it to be. No. I came in with very few expectations, but they were still somehow completely turned upside down. Language was much harder than I expected. From what I read, I must have thought people magically learn languages. Nope. It was harder to get stuff done than I expected. You make a mental list of what you want to accomplish and within one month at site, you throw it out. You make another one, and two months later, you throw it out again. You learn to always expect lots of unexpected delays and roadbumps (this rule applies to transport here as well). The projects you do are a mix of what you want to do, what your community wants you to do, and what your community wants to do themselves. You think you will integrate easily into your community, yet even after almost two years, people make jokes and I still just don’t get how they’re funny (and it’s not the language thing). Don’t get me wrong, despite all of this, I still feel like I am a successful, well-integrated volunteer. Your terms just change slightly. I am so thankful for the family I live with – they are fantastic and I feel very much part of their family. Despite the total lack of privacy, having brothers who will get the bats out of my house makes it worth it. I love the feeling of going to the market, greeting everyone on the way in Bissa, and everyone knowing my name. I feel like I’ve been successful in my work. There’s always those moments of doubt where you think you could leave tomorrow and no one would be able to tell you were there, but writing my final report of my service, I’ve realized I’ve accomplished more than sometimes think (not saying there are still things I wish I had done or had done differently). But the most important are the one-on-one things. It’s not what I do, but what I can get someone else to do. The mom you motivate to change her child’s diet so he’s not malnourished, someone who starts thinking more about HIV prevention because of something you say. We try to look for organizational or institutional growth, but more often as a Peace Corps volunteer, it’s the effect you have on individuals that causes something to change. Certainly there are things I wish I could have done, should have done, but overall, I am very happy with my service. I feel like I’ve been exactly where I was supposed to be the last two years.

Projects in village the last few months have been going well. In March, I finished my second malnutrition rehabilitation program working with the mothers of moderately malnourished children. My counterpart and I changed the format this time. Instead of 12 days in a row, we worked with the mothers over one month, meeting twice a week to make enriched porridge and teach a small health class. I did home visits during the program and talked with the fathers of every child so he can support the mother’s behavior change.

Projects in village the last few months have been going well. In March, I finished my second malnutrition rehabilitation program working with the mothers of moderately malnourished children. My counterpart and I changed the format this time. Instead of 12 days in a row, we worked with the mothers over one month, meeting twice a week to make enriched porridge and teach a small health class. I did home visits during the program and talked with the fathers of every child so he can support the mother’s behavior change.

In addition, I started working with the theatre group to put together a proposal for a hygiene performance. They are asking the mayor’s office for financial support. They wrote a budget, which has usually been our point of contention. They consistently want more money for the performances, I think it’s too much. As they wrote the budget and looked at the total, the president said “Gee, that adds up to a lot,” and lowered their price. We also started writing interior rules and a constitution so they can become an officially recognized group (which means instead of proposing projects, the health district or the mayor’s office can hire them). It was cool because it was one of those moments where I actually felt like I was involved in the capacity building of an entire group. I was there as support, but they took the initiative on the work.

I’ve also continued health education at the high school. I worked with the PE teacher and we did health classes on HIV/AIDS. It’s cool to see the students open up and ask lots of questions. I am constantly amazed by their desire for more information and I wish I had more time with them because they certainly could use more time on health education. I also started doing informal English classes focusing on oral expression. We’ve discussed interesting topics like gender roles, girls education, and forced marriage. For the session on forced marriage, they performed skits. They really enjoyed that. Forced marriage is something that doesn’t happen as frequently here as it used to, but it’s still important to promote the idea that women can and should be involved in their life decisions. We also had a great discussion on girl’s education.

I’ve also worked on more latrine buildings, which I’ll admit hasn’t been one of my favorite projects. It’s logistically very difficult and also difficult to mobilize community members. The latrines were funded by a Small Project Assistance grant that US AID gives Burkina Peace Corps to administer. We’ve built the latrines in public places, like mosques and churches. This also works better than markets for example because there is a specific community it is for and then the pastor or imam can mobilize those communities.

I’ve also worked on more latrine buildings, which I’ll admit hasn’t been one of my favorite projects. It’s logistically very difficult and also difficult to mobilize community members. The latrines were funded by a Small Project Assistance grant that US AID gives Burkina Peace Corps to administer. We’ve built the latrines in public places, like mosques and churches. This also works better than markets for example because there is a specific community it is for and then the pastor or imam can mobilize those communities.

Finally, I attended the Men as Partners conference in May with two community counterparts, Andre and Oussoudoma. They’re community health agents and already tend to be more progressive, so I wanted to bring them because I felt like they’d be great role models for women’s empowerment. The conference focused on how to implicate men in women’s development. We talked about definitions and stereotypes of gender, domestic violence, HIV, and family planning. They were great and really enjoyed the conference. After the sessions, they both came up to me and said, “Erika, this is really important. Really important! We need to do something about this. But we need to start within our families. We start in our houses then other people see us as an example.” It was really cool to see how convicted they were about the topic. We’re planning on doing a gender sensibilisation in July, talking to men and women about what gender is and the stereotypes that limit each gender. They want to start with this because this needs to be understood before change in any of the other topics can happen most effectively.

I also had the opportunity to do a lot of traveling. I traveled with fellow volunteers to Togo and Benin, mostly to hang out at the beach. We left for Lomé on Thursday April 5 and arrived late that night.  We had an exciting trip down, almost leaving behind two in our group at various points during the journey. Once we arrived, it was a whole lot less stressful. We enjoyed a few days at the beach and I celebrated my birthday in Lomé. We found a beach resort (too expensive for us to stay, but you could pay for the pool and beach swimming for the day). We thought we were in heaven! We also thought the same of the espresso at our hotel. We went to one other beach town in Togo before continuing on to Benin. Our first stop in Benin was Ouidah, an old slave trading port, where we visited the museum and the Door of No Return.

We had an exciting trip down, almost leaving behind two in our group at various points during the journey. Once we arrived, it was a whole lot less stressful. We enjoyed a few days at the beach and I celebrated my birthday in Lomé. We found a beach resort (too expensive for us to stay, but you could pay for the pool and beach swimming for the day). We thought we were in heaven! We also thought the same of the espresso at our hotel. We went to one other beach town in Togo before continuing on to Benin. Our first stop in Benin was Ouidah, an old slave trading port, where we visited the museum and the Door of No Return.  (The picture on the left is of the Door of No Return in Ouidah.) The next day, we continued on to Cotonou to get a bus back to Ouaga. One of the highlights there was the Thai food we ate (we don’t have Thai restaurants in Burkina). When we arrived, I saw signs for a half marathon, scheduled for the afternoon I was leaving. I decided to stick around and get a bus the next morning so I could run the half marathon. It was exactly how I expected a half-marathon in West Africa to be. We waited in the sun from noon until 4 pm to register, which was a complete mess of people pushing trying to reach the desk with the computers to register where I was registered by someone who was using a computer for the first time. The race started at 4 pm. (Yes, it is still quite hot at 4 pm.) I helped a Nigerian runner register because she didn’t speak a word of French. It’s turns out she’s an aspiring Olympiad. She was scheduled to run the trials in Canada. She was waiting for me at the end to help her with a taxi back and had obviously been waiting a long time. The most bizarre thing about Cotonou was the crocodile in our hotel. Live crocodile. In a cage, but a cage with openings wide enough for an arm.

(The picture on the left is of the Door of No Return in Ouidah.) The next day, we continued on to Cotonou to get a bus back to Ouaga. One of the highlights there was the Thai food we ate (we don’t have Thai restaurants in Burkina). When we arrived, I saw signs for a half marathon, scheduled for the afternoon I was leaving. I decided to stick around and get a bus the next morning so I could run the half marathon. It was exactly how I expected a half-marathon in West Africa to be. We waited in the sun from noon until 4 pm to register, which was a complete mess of people pushing trying to reach the desk with the computers to register where I was registered by someone who was using a computer for the first time. The race started at 4 pm. (Yes, it is still quite hot at 4 pm.) I helped a Nigerian runner register because she didn’t speak a word of French. It’s turns out she’s an aspiring Olympiad. She was scheduled to run the trials in Canada. She was waiting for me at the end to help her with a taxi back and had obviously been waiting a long time. The most bizarre thing about Cotonou was the crocodile in our hotel. Live crocodile. In a cage, but a cage with openings wide enough for an arm.

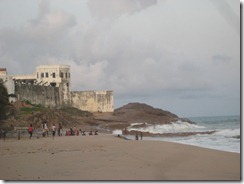

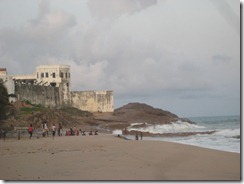

I also traveled to Ghana with a few other volunteers in May.  We spent most of our time in a beach town, Cape Coast. The town was charming and the ocean views were so beautiful. There was a vegan moringa restaurant that had amazing iced coffee! I had some every morning. (Moringa is a tree whose leaves are filled with lots of good stuff, vitamins, protein, etc. It’s used a lot for malnourished children, but everyone can benefit from it. A lot of Peace Corps volunteers work to plant moringa.) One of my favorite scenes of Cape Coast was the fishing boats.

We spent most of our time in a beach town, Cape Coast. The town was charming and the ocean views were so beautiful. There was a vegan moringa restaurant that had amazing iced coffee! I had some every morning. (Moringa is a tree whose leaves are filled with lots of good stuff, vitamins, protein, etc. It’s used a lot for malnourished children, but everyone can benefit from it. A lot of Peace Corps volunteers work to plant moringa.) One of my favorite scenes of Cape Coast was the fishing boats. My first day there, I watched about 10 men in a boat paddle out trying to get past the waves. Compared to some fishing boats in America, these were like ants lined up next to elephants. We also visited a monkey sanctuary, where monkey’s eat out of your hand!

My first day there, I watched about 10 men in a boat paddle out trying to get past the waves. Compared to some fishing boats in America, these were like ants lined up next to elephants. We also visited a monkey sanctuary, where monkey’s eat out of your hand!  Got some great pictures there.

Got some great pictures there.

Like Ouidah, Cape Coast also used to be a slave trading port. We visited the museum in the Cape Coast Castle (old fort). Especially compared to the museum we visited in Ouidah, it was very well organized and the artifacts were very well preserved. Both museums had interesting sections on the African Diaspora. The site of the museum used to be the actual port where slaves were kept before they were sent out on boats, usually across the Atlantic. We were shown the rooms were slaves were kept waiting. Extremely cramped and not hygienic can not even begin to capture the conditions that slaves experienced while in the port (and on the ships). Anyone that gets a chance, I recommend standing in those rooms, standing under the Door of No Return, and trying to grasp the magnitude of the human cruelty, suffering, and injustice that happened in those places that today seem so serene and picturesque.

Despite the beach in Togo, Benin, and Ghana, I’m glad I’m in Burkina Faso. In the handbook, it says the people of Burkina are its greatest assets. We always joked, “Well, it’s that because there is nothing else here.” But traveling to other countries has really made me appreciate Burkina, particularly the people here in Burkina.

On May 26, I ran the Burkina marathon. It was… really hard! Glad I did it, but wow! We started at 6 am, but unfortunately it gets hot here by 7:30. My time was terrible, but I’m just glad I finished! It was a brutal course – we were on a road with lots of cars for a bit, breathing in way too much exhaust. Then we were just running out on pavement towards a random village with a pretty dry landscape on either side. Not that encouraging. But I finished, that was my only goal. About 500 people were registered, but I don’t think 500 showed up that day. Although 15 women were registered, I only counted about 7 or 8 that morning. I’d say at the very most, half of the people that started actually finished the course. Only three women finished, me, Sara (the other PCV), and a Burkinabe female.

My goal for June and July is to enjoy the time I have left here, because, soon, the things I think of now as normal will be gone. This is an experience I will never get again. My favorite chore is going to the pump to get water. I actually really enjoy it. I like hanging out with the women. They mostly speak in Bissa, so I don’t understand much, but I pick up bits and pieces. I can’t really explain it, but it’s just this social ritual that happens every every night. It’s fun to observe and soak it all in. I’ll never get this level of integration again – even just going to the pump is observing a social custom here than any other outsider likely wouldn’t understand. Living with a family has also provided me with experiences that no other foreigner can ever truly experience and understand. I’ve had the chance to not feel like I’m always looking on from the outside, but feel like I’m experiencing something from the inside.